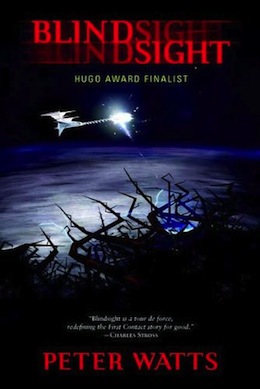

I’m a sucker for space stories. I love ‘em: being out there among the stars, colonizing worlds, travelling FTL, encountering new life forms, fleeing from said life forms. The sci-fi writers that get me the most excited, however—the ones that separate the space wheat from the cosmic chaff—are those who back up their ideas with plausible science, thereby bringing the stars within reach. So it should come as no surprise that I find Peter Watts’s Blindsight so effing awesome.

At its core, Blindsight is a tale of first contact. It’s got everything you could want: a ship named Theseus that “eats” ions to churn them into manufactured matter, an AI captain that keeps its own council, a crew of genetically and mechanically altered transhumans, and an all too believable and terrifying alien anomaly, aptly named Rorschach (the likes of which haven’t been encountered since Clarke’s Rendevous with Rama).

Ironically, however, the element of Watt’s brilliance that truly shines for me is much more terrestrial in nature. Sort of.

Jukka Sarasti is the leader of Theseus’s crew. He’s highly intelligent, calculating, and intimidating. Probably because he’s a vampire. And before you get all agog about vampires in space, that’s not the part that I found exciting. It’s the vampire himself, specifically Watt’s conception of him.

In the story, Sarasti is not some mythical monster with magical powers. Rather, he is an offshoot from our family tree. Around 700,000 years ago, a subspecies diverged from our genetic line, distinctly different from Neanderthals and sapiens: homo sapiens vampiris. Elongated limbs, pale skin, canines, extended mandible. The works. Along with superior hearing, they’ve evolved extra types of cones in their retinas that provide quadrochromatic vision (i.e. infrared eyesight).

If you don’t believe it, just check out the impressive mini-dissertation included in the appendix that serves as a “Brief Primer on Vampire Biology.” The whole take is a re-conception of vampires as predators, not monsters. Like a cross between a shark and a chess grandmaster. Watts’s biological twist on an old archetype is literally hair-raising. And his background in biology provides both a hair of believability and credibility. (He holds a BS, an MS, and a PhD.)

The most fun part is how Watts takes everything you know about vampires and retrofits it all with a sound, scientific explanation. In developing a radically different immunology, vampires exhibited a stronger resistance to prion diseases (you know, the ones you get from cannibalism). So, that’s how they can eat people. Awesome.

Somewhere during their evolution, vampires “lost the ability to code for y-Protocadherin Y,” a protein they desperately need. Guess who’s the only the viable production source? So, that’s why they eat people. Perfect.

While human prey is a prolific food source, it is a slow-breeding one. As anyone who’s studied basic ecology knows, if predators’ dining habits outstrip its prey’s mating habits, they run out of food. Quickly. In order to sustain their food source and themselves, vampires developed a knack for hibernating (think more lungfish than bear). These periodic respites gave the human population time to, well, repopulate. Or as the vampires saw it, restock the shelves. Hence, vampires affinities for long naps, in dark quiet places.

The most creative and downright genius revamping (sorry, I couldn’t resist) Watts creates is the “Crucifix glitch.” Yes, in the world of Blindsight vampires hate crucifixes, but not for the reason you’re thinking. It has nothing to do with his Holiness. Remember when I said vampires have advanced eyesight and whatnot? Well, there’s a downside to that. Vampires are natural creatures that evolved for thousands of years to maximize their perception and pattern matching abilities (it helps with hunting). There are two problems with this: 1) with evolution, neutral traits become fixed in small populations; 2) there are no right angles in nature. So vampires developed a glitch. When the synapses that process vertical and horizontal stimuli fire at the same time, across a large enough visual field … vampires have grand mal-like feedback seizures. So with a little Euclidean architecture, humans took the upper hand and stamped vampires out into extinction.

In this fantastic story, Watts makes vampires real and subsequently, scares the bejesus out of me. And yes, I do know that I’ve ignored the looming question: if vampires are extinct, then how did Sarasti end up on a space ship in the future? For that answer, you’re going to have read Watts’s terrifyingly plausible tale.

Joshua V. Scher is a recent transplant from New York City to the Hollywood hills, where he is continuing his transition from writing for the stage to the screen, both theatrical and television. His film, I’m OK, is in postproduction and slated for a festival run in 2016. The cinematic adaptation of his play The Footage was developed by Pressman Film. Scher collaborated with Joe Frazier and Penny Marshall’s Parkway Productions on the Joe Frazier biopic Behind the Smoke. He also worked with Danny Glover and Louverture Films on Scher’s original TV pilot, Jigsaw. His works for the stage include Marvel, Flushed, and Velvet Ropes, as well as the musical Triangle. He holds a bachelor’s degree with honors in creative writing from Brown University and a master of fine arts degree in playwriting from Yale University. Here & There, out now from 47North, is his first novel.

Ok, you convinced me. Thanks a lot – added to amazon cart. =)

I tried this on my Kobo. I heard great reviews, and the entire storyline sounded fantastic. First contact – yes please, hard sci-fi…yes. Cdn author…bonus! However………I just could not get into it, and really…I can honestly say that I did not finish it. I want to give Watts another try, and I may restart this some day.

I dunno, the right-angle thing felt pretty handwavey. My first reaction was “what about trees on the plains? or just trees and branches?” I’m biased here, though, since I absolutely hated the sort of pet theory about consciousness that ended up being the point of the story. I’ve enjoyed some of Watts’ other work, but haven’t been able to go back to him after this one.

But maybe my strong reaction in one direction means other people will love it. That seems to be how it goes for a lot of stories. ;)

@3: For what it’s worth, the sequel, Echopraxia, explicitly tackles and explains away the ‘trees on a horizon’ thing (I can’t recall it in specifics, but it was plausible-enough sounding for my tastes). As for branches, I can’t think of many that are near perfect right angles, and areas where such plants exist would just naturally be areas where vampires weren’t.

I thought this was by far the strongest sci-fi novel to come out in a 3-5 year window around when it was published. The concepts of consciousness as a parasite, and non-augmented/vampire/AI humans delegated to the dustbin of history were both way edgy, which is what top SF is always about: finding the edge, and pushing it, hard.

Outstanding book. The sort-of sequel, Echopraxia, is equally good.

OK, I think 6 was mine and I’m slightly confused about why it was removed – I was just pointing out that if you look at Peter Watts’ personal website there’s a very entertaining slide show about the development of the Blindsight vampires (narrated by him, in the persona of an ambitious and utterly amoral scientist). Maybe it was the link?

@8 – comment 6 wasn’t yours, and I actually don’t see any held comments from you on this post, so maybe it just didn’t go through? Feel free to repost.

ghostly1 @@.-@:

As for branches, I can’t think of many that are near perfect right angles

Actually, if I look out the window of my office during winter, I can see half a dozen right angles created by branches crossing in front of other branches. There are lots of other projected intersections that aren’t right angles, of course, but there are enough branches and enough trees that some of the crossings will end up as right angles, or near enough as makes no difference.

I’ve just started Echopraxia, so I’ll see if the “trees-and-horizon” thing crops up.

#10: Yes, but remember, it’s not JUST intersecting right angles… it’s intersecting right angles that a) take up a large enough amount of the visual field, and b) are oriented towards the horizontal/vertical to the person viewing them, and possibly other conditions (it might have to stand out from the background, so that if two branches cross in a right angle, but there are other branches crossing them all over at another right angle, it might not trigger). Add to that the possibility that they might have some discomfort but not full-on seizure if they get close to fulfilling a) and b), so they can avoid getting themselves in situations/head orientations where they trigger it (but can still be surprised with one out of nowhere and be unable to break into a building made of right angles), it doesn’t strike me as enough of a problem to bother me as a serious flaw in the concept.

(Now, slightly more problematic for me is the fact that this prehistoric predator has characteristics that explain their aversion to crosses, which was only added to the lore in the last couple hundred years or so while vampire legends have existed long before that, but I go with it for the rule of cool aspect). Incidentally, if you’re allowing for that, the idea of “pre-emptive avoidance” might also help explain some of the OCD qualities of vampires… sure they can cross running water, but maybe there’s a couple logs that form a cross on the other side, so when somebody’s running from them, the vampire stops suddenly and looks for another way around, and their would-be victim assumes, “A ha, water! They must not be able to cross it!” and shares the tale.

I have to admit that I found the vampire scenario clever, but a little hard to take seriously. For example, the scenario of “lost the ability to code for Protocadherin Y, and so they eat people in order to get it” seemed a bit backward. As I understand such things, the plausible sequence is: 1. Animal species starts regularly eating things that contain substance X, which is also being made internally. 2. A mutation knocks out an animal’s ability to make X, but that’s OK, because it’s already ingesting lots of X. 3. The mutation spreads through the gene pool, either due to genetic drift in a small population, or possibly because animals with the mutation are slightly better off not wasting the resources and energy on the machinery for making X internally, since they’re getting enough from their diet.

http://thehumanevolutionblog.com/2014/09/13/why-humans-must-eat-vitamin-c/

So we could have vampires lose the ability to make some essential protein (e.g., “protocadherin Y”) if they were already routinely eating humans. But “they lose it, and so they turn to eating humans” won’t really work.

Other problems with the “vampires desperately need protocadherin Y” idea (which imply some rather odd things about vampire predation habits):

1. The gene coding for this protein is only found on the Y chromosome. (And is apparently unique to humans, which is why Watts picked it; other protocadherin proteins are found in lots of mammals, so the “must eat humans” restriction wouldn’t apply.)

So it’s hard to see how female vampires would “desperately need” something that female humans get along just fine without.

(So vampires are actually like mosquitoes, except for a gender switch: only male vampires attack people…)

2. Also, there’s not much point in eating/drinking from female humans, since they won’t have the protein.

3. This protein is important for fetal development of the brain (this is true of the similar X-chromosome-based protocadherin proteins); how does the vampire fetus get the protein? (The only plausible answer is: “from their mothers”; so we can deduce that female vampires do attack [male] humans, but only when they’re pregnant — and only then if they’re pregnant with a male fetus…)

Vampires: Biology and Evolution (on youtube)

The flash version is up under http://www.rifters.com/blindsight still.

I mostly agree with @12 and @13 (though, I’d point out that the vast predominance of Vampire lit, at least to the latter part of the 20th century, didn’t have female vampires, or if it did they were frequently not seen sucking blood; though otgh one of the first, Carmilla, did have a female vampire).

My real problem with Blindsight was that the whole (very good) book, just seemed like an excuse to explain vampires. Sarasti didn’t actually need to be a vampire for the story to work.